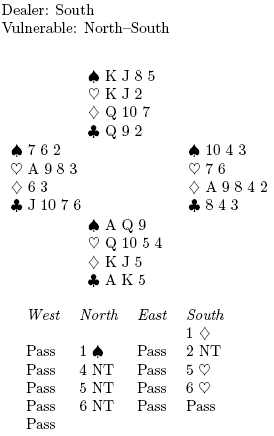

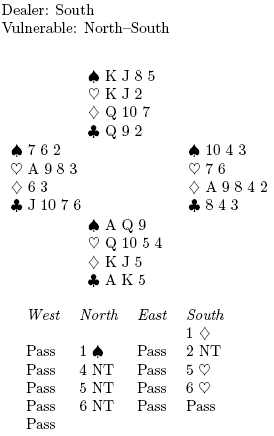

The following deal occurred at the Junior National Bridge Championship held between 28 Feb and 2 Mar 2007 in Surat. The IITM team comprising Guthi, Kedar, Ram, and Tota, finished third, just two VPs below the runners-up. Guthi and Kedar produced a shocking result on the following board against an IIT Kharagpur pair. (Since the deal was not recorded on paper and is here reproduced from Guthi's memory, some unimportant details may be wrong.)

After some hyper-aggressive bidding by Kedar (North), Guthi, South, declared an entirely reasonable 6 NT. The contract makes whenever the pack is missing a red ace. Guthi knew there were additional chances in finesses.

The lead was a spade and declarer won on the table, to lead a low diamond. South's 5 ♥ had shown two aces. East put two and one together, getting four, and knew that West held no ace. He correctly ducked the diamond to let the weird finesse against the jack or the king lose.

Declarer took the jack and led a low heart. West too, meanwhile, had put two and one together and knew that East held no ace. He rightly ducked the heart so that the jack could lose to the queen.

Of course, it didn't, and declarer played ♦ 10 from the table now, for another finesse. East was no doubt seized by fears of declarer's long diamonds getting established. So he cleverly ducked again to leave declarer stranded in dummy.

By now, South was convinced that one or other chance had come good and was anxious to repeat the mixture, so he played another heart. West suddenly spotted the winning defence. Up he went with the ace and reached for the diamond that wasn't there. Twelve tricks for +1430 and 13 IMPs.

I suppose defenders were miffed at their bad luck—both aces were onside for declarer. Guthi, meanwhile, was probably disappointed he couldn't take three “finesses” each in the red suits to bag thirteen tricks.

North's 4 NT was hasty. First, the combined hands have 30–31 points—not enough for a notrump slam, especially given the 4–3–3–3 pattern. Second, are you wondering why he bid slam knowing they were off two aces? Because 5 ♠, he figured, might be passed by South, since North bid spades first. (If spades had been unbid, 5 ♠ would have asked South to bid 5 NT.)

Guthi subsequently clarified that he would not have passed 5 ♠, because with long spades, responder's correct action is to start out by transferring to spades after opener's 2 NT rebid (by bidding 3 ♥). Anyway, North should think about this before bidding 4 NT. Since he plans to bid 6 NT after a 5 ♣ or 5 ♠ response to Blackwood, and will be forced to bid 6 NT even after a 5 ♥ response, he must blast to 6 NT (A 5 ♦ response is impossible on the bidding). In that case, even a non-duckling West might fail to set the contract. Of course, five-notrump king-asking Blackwood after receiving the bad news is third-degree masochism.

Last, how do you play the hand in 6 NT? It is safe to assume the aces are split, because the contract wasn't doubled (yes, even if you're not on lead, you must double an opposing 6 NT holding two aces, because it's highly unlikely that (i) declarer can find twelve top winners in two suits, and (ii) partner will lead a wrong suit). In addition, you must make the assumption that both defenders were sleeping during the bidding, otherwise the contract is down the moment dummy hits the table. Because even one alert defender can tip his partner off by cashing his ace at the first opportunity.

Since you need five (yes, ruefully, five) red winners, you must get them immediately. Guthi's line is probably the only that had any chance (some chance!). You have to take a view on who holds which ace. One might think that there's a slim chance that West is the kind of doublomaniac that would double either of the two Blackwood responses to show his heart ace (not unusual doublomaniacal behaviour), forgetting that he would be on lead. And that since he didn't he doesn't hold it. Pretty thin, but it's something. However, as you can see, it leads to the wrong conclusion on this layout.

Guthi evidently needed none of this, because, like a magician inspired by the devil, he turned two normal healthy human defenders into ducklings and made his contract with a swagger.